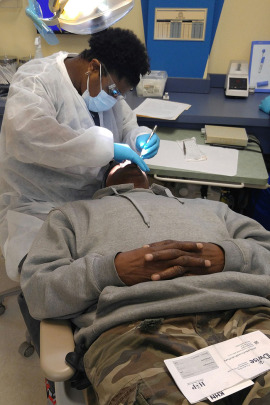

Reginald Rogers of Gary, Indiana, pays $1 a month for dental coverage through Healthy Indiana. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

GARY, Ind. — Reginald Rogers owes his dentist a debt of gratitude for his new dentures, but no money.

Indiana’s Medicaid program has them covered, a godsend for the almost toothless former steelworker who hasn’t held a steady job for years and lives in his daughter’s basement. “I just need to get my smile back,” Rogers, 59, told his dentist at a clinic here recently. “I can’t get a job unless I can smile.”

Rogers is among the more than 240,000 low-income people who gained health coverage in the past year when Indiana expanded Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act. Rogers pays $1 a month — a fee that is a hallmark of the state’s controversial plan.

Healthy Indiana pushes Medicaid’s traditional boundaries, which is why it has the attention of other conservative states. The plan demands something from all enrollees, even those below the poverty line. The poorest Hoosiers can get coverage with vision and even dental benefits, but only if they make small monthly contributions — ranging from $1 to $28 — to individual accounts similar to health savings accounts. Individuals who fail to keep up lose the enhanced coverage and face copayments. Others who are above poverty can temporarily lose all coverage if they fall behind on contributions.

If that sounds more like commercial insurance, it’s by design. So is the plan’s tough-minded approach to paying for low-income Americans’ health care.

Proponents say the strategy makes Medicaid recipients share financial responsibility for their care, which they say will save Indiana money by reducing unnecessary services and inappropriate emergency room use.

Several states, including neighboring Kentucky and Ohio, are looking at Indiana Medicaid as a possible model.

Detractors worry that its complexity could make health care harder for the poor to access — the opposite of a core goal of expansion. There is no proof that the state is yet saving money or that its approach is making beneficiaries healthier.

“Other states have looked at it, but the Obama administration has made it pretty clear that Indiana is going to be a test case and much evaluation will need to be done before they approve any more like it,” said Matt Salo, executive director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. No other program has been allowed to require health spending accounts, much less threaten a loss of coverage for not paying in, he noted.

Since Indiana’s expansion began in February 2015, more than 235,000 previously uninsured able-bodied adults have signed up. As of late February, the plan covered more than 370,000 people total, many with extremely low incomes. Another 190,000 adults are eligible but not enrolled, according to state estimates, though some who are above the poverty line may be in subsidized private plans.

Michelle Stoughton, senior director of government relations for Anthem, says the response to date represents success. Anthem is one of three private insurers providing coverage under Healthy Indiana. “What we heard for years … is that these people won’t pay and don’t have the ability to pay,” Stoughton said. “But this has turned those arguments around and been able to show that people do want to be engaged.”

Sisters Tanya Flynn, left, and Debra Crawford wait to be seen at Ezkenazi Hospital outpatient center in Indianapolis. Both are Healthy Indiana members. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

The ACA created both the financial means and the opportunity for Healthy Indiana. The 2010 law paid for states to expand Medicaid by enrolling all adults under 65 who earned up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level — about $16,394 annually for an individual. The federal government will have absorbed the full cost of newly eligible beneficiaries from 2014 through this year. After that, its share falls gradually to 90 percent in 2020 and beyond.

As did most GOP-controlled states, Indiana initially balked at the offer, with officials citing concerns about Medicaid’s costs and effectiveness. Now they believe they’ve found the solution. Republican Gov. Mike Pence sees the plan as a model for others.

Healthy Indiana “has established a new health care paradigm in Indiana; rooted in consumerism and personal responsibility, Pence said in late January as he marked the plan’s first anniversary. It has federal approval until January 2018.

With Healthy Indiana, enrollees can choose basic coverage that requires no monthly fee but excludes dental and vision. Or they can pay the monthly fee for enhanced coverage with those benefits. Their contributions go into what’s called a POWER account — the acronym stands for Personal Wellness and Responsibility — that is used for the first $2,500 of medical expenses each year. Indiana pays the bulk of that, and if expenses exceed $2,500, the state also pays for additional services at no cost to the individual.

The optional dental and vision coverage, which many states don’t offer to adults on Medicaid, is proving a powerful lure. Nearly 75 percent of Anthem’s Healthy Indiana members visited a dentist, and 65 percent sought vision care in the first three months of coverage, Stoughton said.

Members who don’t maintain their monthly contributions are penalized, but the punishment is tied to their income level. A person above the poverty level — $11,880 in annual income — can be unenrolled for six months from all coverage. Someone below that level who stops paying will lose the dental and vision coverage and face copay charges of up to $8 to see a doctor or fill a prescription. Just over half of program enrollees have annual incomes below $600, according to state figures.

Recipients who make their contributions face no other health care costs. They can also lower future contributions by getting recommended preventive care, such as cancer screenings and checkups.

The hook may be working. State figures show a 42 percent drop in emergency room use in 2015 among people who were on traditional Medicaid and shifted to the new program. Cesar Martinez, CEO of health plan MDwise, said about 80 percent of its 105,000 Healthy Indiana members have used primary care at least once. That’s a third higher than the typical figure in other states’ Medicaid programs.

The hook may be working. State figures show a 42 percent drop in emergency room use in 2015 among people who were on traditional Medicaid and shifted to the new program. Cesar Martinez, CEO of health plan MDwise, said about 80 percent of its 105,000 Healthy Indiana members have used primary care at least once. That’s a third higher than the typical figure in other states’ Medicaid programs.

So far, 70 percent of enrollees are making the required contributions to get Healthy Indiana Plus with dental and vision coverage. “That’s 70 percent more than folks in Washington told me would make those contributions,” Pence said in January.

And overall, 94 percent of people with POWER accounts have continued to pay into them, state officials said. Most do so through debit cards, money orders or a free payment service at Wal-Mart stores in the state.

Yet since the state began enforcing the program’s stick provision in May, about 2,200 people with incomes above poverty have lost coverage because they didn’t pay their monthly fees.

Officials say their surveys show nearly nine in 10 Healthy Indiana members are satisfied or very satisfied with their coverage. Most residents interviewed at health clinics in Indianapolis and the state’s northwest corner, its poorest region, shared that opinion.

Byron Yeager Jr.’s decision to enroll last spring proved prescient. Not only did he get his first pair of new eyeglasses in many years, as well as dentures to replace his rotted teeth, but after he suffered a stroke in June, Medicaid also paid for his hospitalization and rehabilitation care. All of that for his $1 a month.

“It was a stroke of luck,” said Yeager, a 60-year-old former construction worker who lives in Indianapolis.

Hospitals and doctors supported the Healthy Indiana plan because both got substantial raises from Medicaid. Indiana agreed to increase hospitals’ rates by an average of 20 percent and doctors’ pay by an average of 25 percent. As a result, Medicaid has gained more than 5,300 providers in the past year, and patients report few problems getting care.

What’s not clear yet is whether Healthy Indiana is paying off for the state and worth modeling in others. Some conservative groups say the program may be more expensive than traditional Medicaid because it provides dental and vision care and better compensates providers.

“I’m not against expanding coverage, but people should know it comes at a cost,” said Josh Archambault, senior fellow for the conservative Foundation for Government Accountability.

Other critics worry that the monthly payments and the more complicated structure of people’s coverage will keep the poor from getting care.

Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, said the red tape in Healthy Indiana exceeds that of any state’s Medicaid expansion. Few third parties, such as employers and nonprofit groups, have offered to help individuals cover their monthly contributions, as the state had hoped, Alker noted.

She questions why so few eligible people above the poverty level have not enrolled. Many may have signed up for subsidized Obamacare marketplace plans in 2014 and could now be paying more than necessary, she said.

“It’s premature for Indiana to take a victory lap,” Alker said.

This article was reprinted from kaiserhealthnews.org with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent news service, is a program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan health care policy research organization unaffiliated with Kaiser Permanente.